The Premonition of a Dusty Dreamscape: Revisiting 1956

Before NASA had even etched its name in history or immortalized the human footprint on the moon, our celestial companion was but a canvas for speculation derived from distant observations. In the year 1956, Hal Clement, a luminary in the cosmos of science fiction, gifted the world with his novella, “Dust.” It spun a tale of astronauts venturing into a lunar crater to investigate a mysterious dimming of starlight near the moon’s horizon, a phenomenon hypothesized as a lunar atmosphere.

Astronauts’ Query Amidst Celestial Dust

In Clement’s orbit of imagination, the astronauts deduced that the ethereal lunar mist couldn’t be an atmospheric layer as once supposed, but a dance of dust particles skittering across the moon’s surface. The narrative wove a convincing dialogue, pondering the outcome of the moon’s filthy, conductive surface—a domain where dust is ever-aroused, ever-settling, and through its perpetual friction, ever-charged.

“What marvels would be wrought,” one astronaut mused, “if a crater, hundreds of kilometers in girth and several kilometers high, bore this electric charge?” The proposed spectacle Clement envisioned was akin to a grand fountain of dust, rising and swirling under the sun’s gaze, driven by static forces.

Of Apollo and Phenomena: The Vision Meets Reality

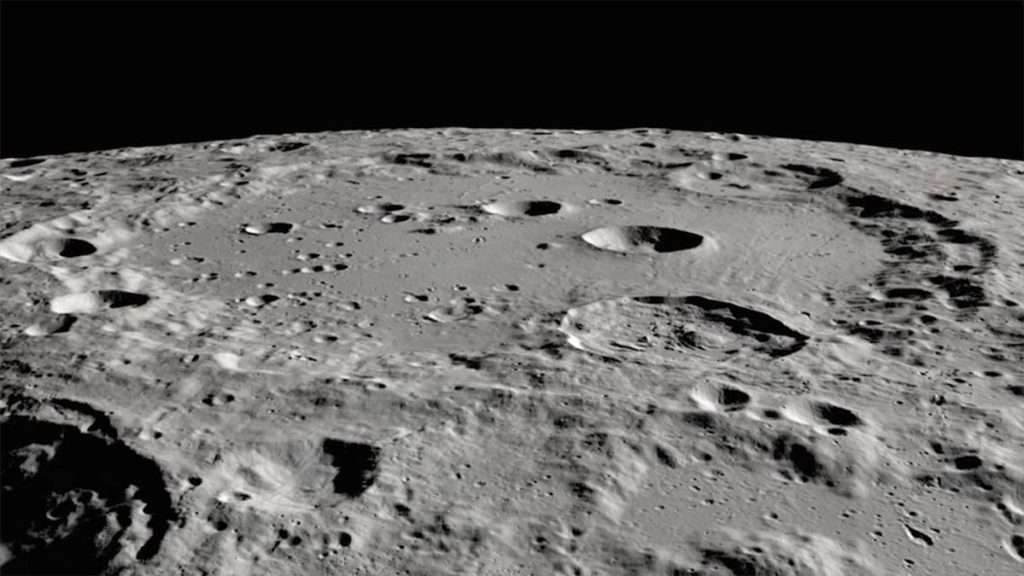

Unknown to Clement, his fantasy bore striking resemblance to the later Apollo missions’ lunar photographs and the celestial wonders witnessed by the astronauts themselves. Before the Apollo 11 crew set foot on lunar soil, earlier surveys had transmitted images back to Earth—portraits of dawn’s pallid light perpetuating until nightfall, and horizons not razor-sharp but softly blurred, where sky and surface meshed indistinctly.

The astronauts of Apollo 17, weaving around the moon, beheld what they sketched as “streamers,” “horizon glow,” or “twilight rays”—phenomena also echoed by their colleagues aboard Apollos 8, 10, and 15.

Charged Particles and Fountains of Light

Much like Earth’s twilight gleam, these lunar illuminations were thought to be a kin of atmospheric scattering—a scattering impossible on an airless celestial body. How could dusty particles hang aloft persistently? Why wouldn’t lunar impacts settle swiftly back down?

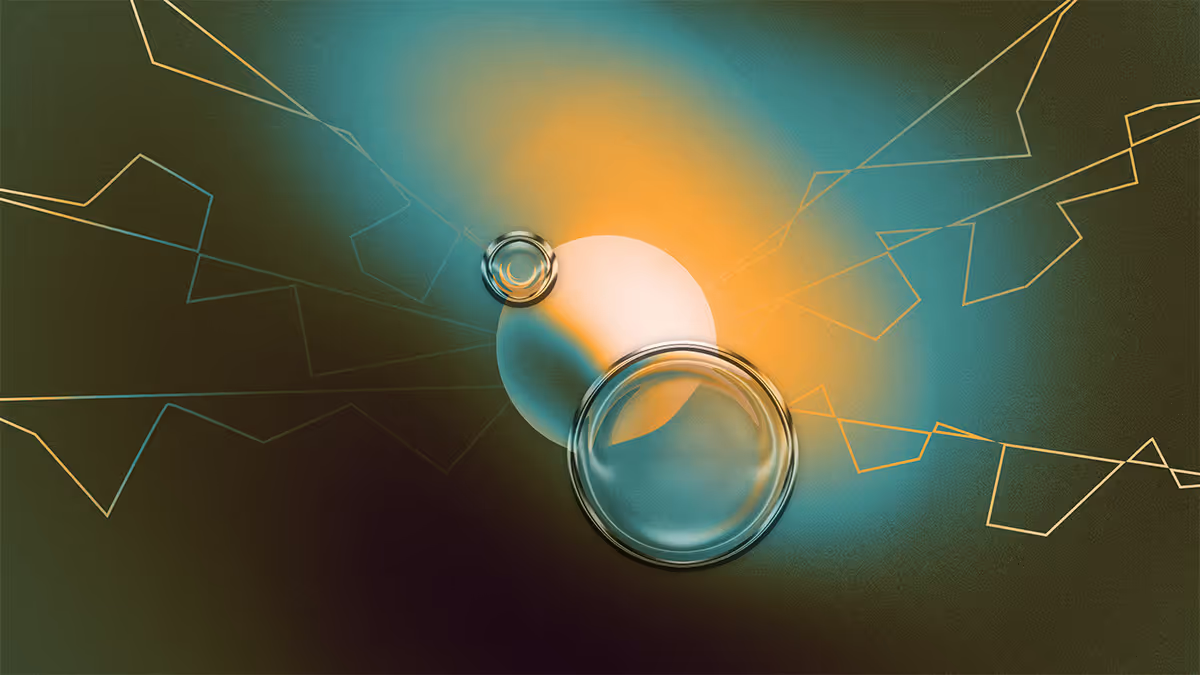

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center physicists pursued clarity, devising the “Dynamic Fountain Model” to capture the essence of lunar dust mobility. This model revealed a perpetual “atmosphere” above the lunar surface, not of air, but of ever-moving charged dust—a figurative fountain of particles that rise and fall ceaselessly.

Earthly Analogies: The Sparks that Answer the Lunar Riddle

Clement’s story suggested friction-induced electrification, but lunar dust’s charge is bestowed by the sun itself: photoelectric captures of sunlight resulting in static, compounded by the electrically charged solar wind particles. The echo of our earthly experiences, where balloons rubbed against hair stand strands on end, elucidated the moon’s mystery—charges attract and repel in the void as they do within our grasp.

A Symphony of Silence: The Ever-Present Lunar Cascade

On the moon’s dayside, dust particles ascend, charged to repulsion and hovering meters to kilometers above the terrain. By night, they carry a negative charge—solar wind’s gift—and rise higher still, an invisible spectacle save for the absent sun’s light.

At the twilight divide, as on Earth, a potent electrical field is surmised, prompting dust to stream laterally through the liminal space, leaving shadows and highlights playing across the lunar daybreak—ethereal curtains illuminated by shifting lines of dawn, marvels unseen by human eyes yet sketched by those who ventured near.

Beyond Twilight: The Quest Continues

Goddard researchers now delve deeper, questing after lunar dust fountains and their enigmatic influence. In shadows of deep craters lies the moon’s water—a treasure for future colonies. But amidst a maelstrom of charged particles, how shall humanity traverse this dusty dreamscape?

Discussion about this post