Laser Beams in Low Earth Orbit: A Technological Solution with Political Consequences

In 2025, SpaceX’s latest orbital initiative—an experimental “space junk laser” platform—entered its operational testing phase above Earth. Its goal, at least on paper, is noble: reduce the growing threat of orbital debris that clutters low Earth orbit (LEO) and endangers satellites, astronauts, and future missions. But what began as a technological marvel quickly raised red flags across international defense and policy circles. At the core of the controversy lies a single troubling question: What happens when a cleanup laser looks too much like a weapon?

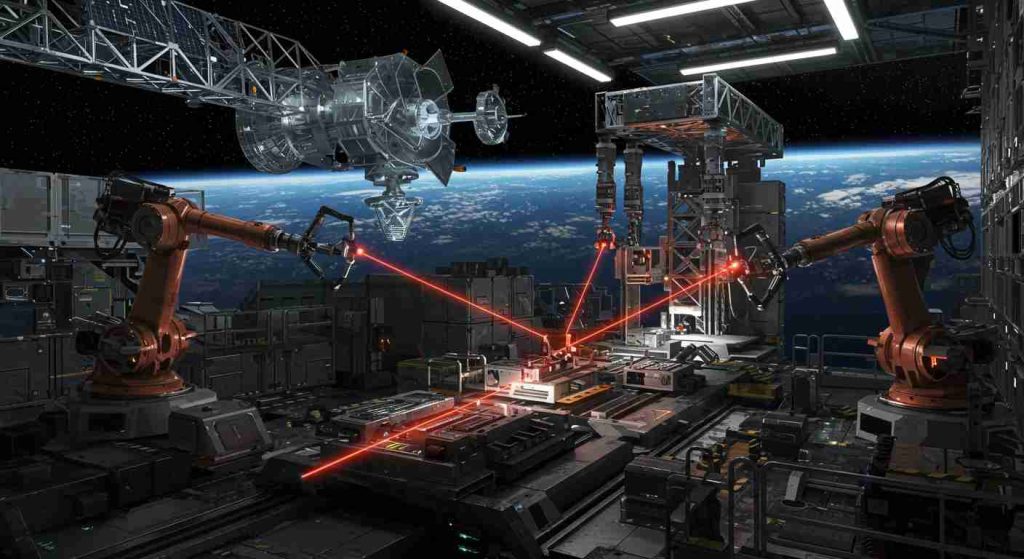

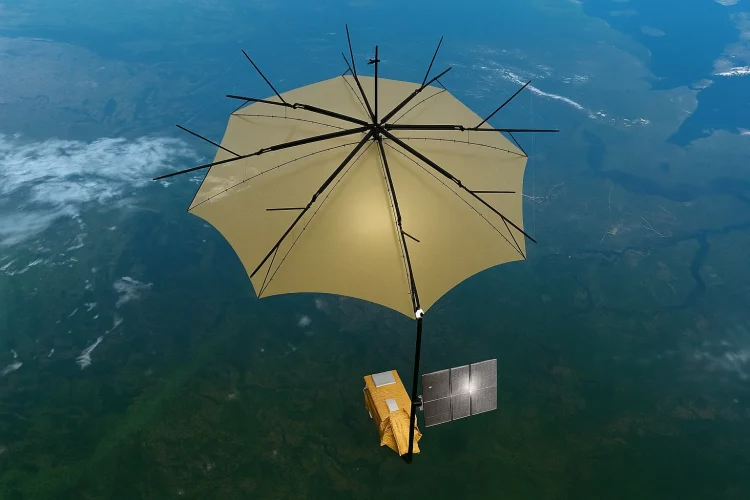

The technology itself is advanced but straightforward in principle. Using a high-powered, ground-based or satellite-mounted laser, the system targets small pieces of defunct satellites, rocket boosters, or collision fragments. The laser vaporizes the surface of these objects with brief, directed pulses, creating microthrust that nudges the junk into a lower orbit where it eventually burns up in Earth’s atmosphere.

This momentum transfer method has been under study since the early 2010s, but SpaceX’s integration of machine vision, autonomous targeting, and orbital maneuvering through Starlink-linked platforms represents the first semi-operational deployment of such a system at scale. Its real-time targeting algorithm is trained to recognize dangerous debris, prioritize proximity to active satellites, and select optimal pulse sequences.

But therein lies the risk: what if the AI mistakenly targets an active satellite—or worse, a military reconnaissance platform cloaked as a weather array?

The Slippery Slope of Misidentification and Misinterpretation

Space is already a foggy domain when it comes to intent. Many civilian satellites are dual-use, capable of both scientific data collection and surveillance. A seemingly harmless maneuver by one satellite near another can easily be misread as an act of aggression. Add a laser system into the mix—one that emits energy bursts powerful enough to alter trajectories—and the potential for international crisis escalates exponentially.

In early field tests leaked to orbital monitoring forums, SpaceX’s prototype was seen engaging with debris less than 50 meters from a Brazilian CubeSat conducting solar wind research. While no damage was reported, the incident sparked fears among smaller space agencies that their micro-satellites, lacking military-level shielding and precise tracking transponders, could be mistaken for junk by SpaceX’s targeting algorithm.

Worse yet, there’s speculation that the system could be repurposed for offensive anti-satellite operations. A laser capable of deorbiting junk could, under only slightly modified parameters, disable or destroy active satellites. The blurred line between utility and aggression puts the onus on the operator—SpaceX in this case—to ensure flawless judgment, both by its onboard AI and its mission parameters.

Military strategists warn that an accidental deorbiting of a foreign communications or reconnaissance satellite could easily be perceived not as a technical mishap but as a preemptive strike. The speed of response in space is minimal, but the implications are global. One misfire, mislabeling, or mistranslation could ignite a chain of suspicion that diplomatic channels might not be fast enough to contain.

International Law in Orbit: A Legal Vacuum Above the Clouds

Under current space law, especially the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the 1972 Liability Convention, nation-states retain liability for objects they launch into space. However, these agreements predate the era of privately-operated orbital lasers. Nowhere do they directly address non-kinetic interventions like debris nudging or vaporization.

Worse, there is no universally agreed-upon definition of what constitutes “harm” in the context of non-collisional satellite interference. Does the use of a laser that causes a minor trajectory shift of a foreign satellite count as an attack? Can a nation invoke Article 51 of the UN Charter—its inherent right to self-defense—if one of its space assets is struck, even accidentally?

With no court in space and no standard arbitration process for satellite conflicts, what happens is determined more by perception than protocol. The United States may view SpaceX’s laser tests as civilian R&D, but other countries, particularly geopolitical rivals, may see them as unregulated extensions of national power.

The legal ambiguity gives cover for escalation. A nation claiming its satellite was damaged—or even just threatened—can invoke defensive measures under the guise of responding to aggression. Given the speed and opacity of orbital incidents, the fog of misunderstanding could turn a technological demonstration into a flashpoint.

China’s Response: Defensive or Competitive?

China, ever alert to strategic vulnerabilities in its increasingly crowded LEO networks, responded quickly. Within weeks of the first SpaceX laser tests, Beijing announced the deployment of a “defensive satellite net” around its sensitive Earth observation assets. Officially described as a mesh of AI-enhanced micro-satellites capable of identifying and shielding key national platforms, the constellation raised eyebrows across defense analysis circles.

Dubbed the “Mirror Shield” by Chinese state media, the system reportedly includes deployable polymer layers that scatter or absorb low-intensity laser pulses, as well as reactive maneuvering capabilities. But more provocatively, some open-source intelligence suggests it includes jamming modules capable of disrupting targeting signals from other satellites.

Western analysts debate whether China’s move is strictly defensive. Some believe it’s a strategic testbed for future counter-space capabilities under the guise of passive protection. The deployment timeline—rushed, opaque, and heavily guarded—suggests urgency beyond civilian concern.

Meanwhile, Russia has remained silent, but internal memos from ESA satellite operators cite interference from “unknown LEO signatures” consistent with laser calibration emissions near Russian orbital zones. Whether intentional or incidental, these interactions illustrate the geopolitical volatility of deploying lasers into shared orbital space.

The Broader Picture: Cold War Redux in Orbit

With the militarization of space proceeding faster than regulatory consensus, SpaceX’s junk laser may go down as a moment that punctuated a quiet transition into orbital realpolitik. Like GPS once did for satellite navigation or drones for aerial warfare, lasers in space may shift not just how things are done—but how the world perceives who holds power above Earth.

It’s no longer about who has the most satellites, but who can influence or disable the satellites of others without direct collision. Lasers, particularly those marketed as “cleaners,” provide a plausible deniability mechanism for satellite interference, sparking debates not just in parliaments and boardrooms, but on the ground in military command centers.

In this environment, miscommunication is as dangerous as intent. An AI system wrongly labeling a functioning satellite as debris isn’t just a technical glitch—it’s potentially a casus belli.

Conclusion: Tech That Outpaces Trust

The challenge with SpaceX’s space junk laser isn’t that the technology is fundamentally flawed—it’s that it assumes a level of international trust that simply doesn’t exist in today’s fragmented geopolitical climate. When one actor, even with good intentions, holds tools that others interpret as threats, conflict becomes a matter of perception rather than action.

Until new treaties explicitly define the line between maintenance and interference, every laser fired into orbit carries with it a diplomatic shadow. In the absence of shared protocols, humanity faces a scenario where an effort to clean up our orbital highways could unintentionally spark the very kind of terrestrial conflict we once believed space technology would help avoid.

The question isn’t whether these lasers work—it’s whether they can be trusted. And trust, unlike satellites, cannot be launched. It must be negotiated, safeguarded, and constantly reaffirmed in a world racing ahead with technology but limping behind in diplomacy.

Discussion about this post