A Radical Rethink of End-of-Life Electronics

In 2025, a groundbreaking innovation is transforming how we think about smartphones—and waste. Gone are the days when old phones gathered dust in drawers or turned into toxic landfill; the new generation of self-destructing devices is designed to biodegrade on cue. Leading this wave is a collaboration between Samsung and Xiaomi: smartphones built on programmable biopolymer circuit boards that can disintegrate into compostable components once their service life ends. This initiative positions e-waste reduction not as a distant goal, but a built-in feature. It’s a radical shift—one that aims to make every user also a steward of the environment.

Biodegradable Electronics: How It Works

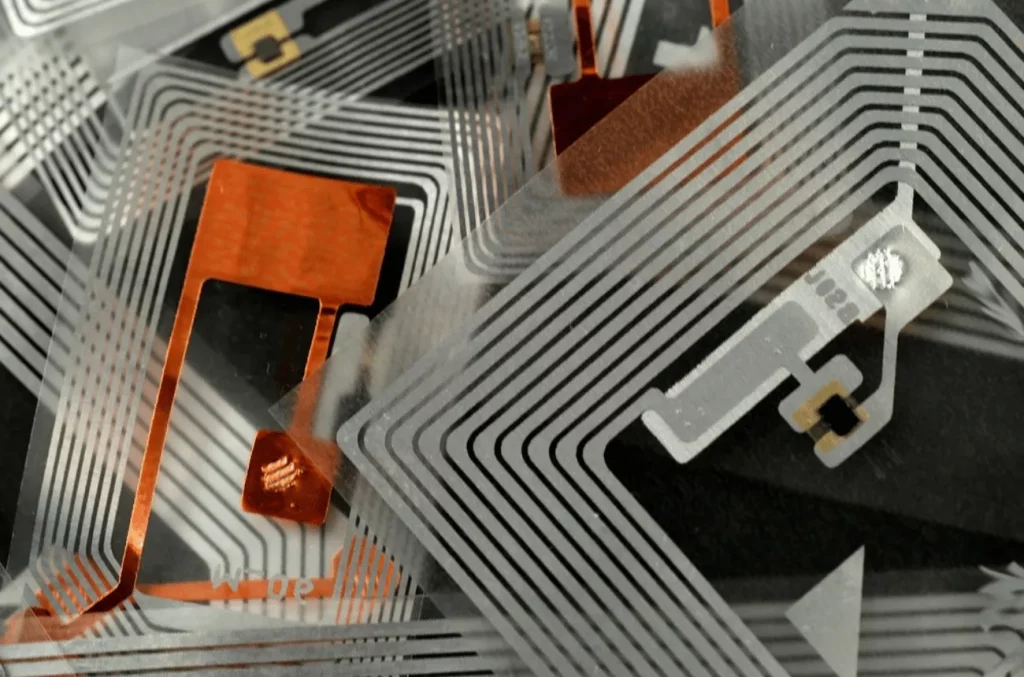

Traditional smartphone circuit boards are made of rigid, toxic plastics layered with metals and solder—a combination that makes recycling difficult and hazardous. Samsung and Xiaomi’s new approach replaces conventional printed circuit boards (PCBs) with biopolymer-based substrates. These are made from chitosan—derived from crustacean shells—and cellulose nanofibers sourced from sustainable forestry. Conductive pathways utilize crystalline silk proteins infused with silver nanowires, creating a wiring system capable of high-speed digital performance.

At the heart of the innovation is a programmable degradation switch embedded in the motherboard. Activated either via software (through an OS command and verification key) or remotely by carrier authorization, the switch begins a controlled enzymatic breakdown. A layer of encapsulated enzymes—specifically cutinase and laccase—remains dormant during the normal life of the device. Once triggered, they dissolve the biopolymer matrix, releasing sequestered acidic agents that digest adhesives, coatings, and polymer substrates. Within 5 to 7 days, core components reduce to harmless organic remnants—sugars, peptides, and microscopic trace minerals safe for compost or land applications.

This technology was first conceived in advanced materials research labs in 2022, but it wasn’t until late 2024 that Samsung and Xiaomi formed a public-private consortium to industrialize the process. By 2025, the first certified biodegradable smartphone models hit test markets in Europe and Japan—a pilot for wider global adoption.

Environmental Promise vs Nano-Pollution Peril

The eco-appeal of self-destructing phones is obvious: no toxic landfill waste, minimal recovery costs, and a life cycle that ends cleanly. Proponents highlight the potential to reduce plastic e-waste volumes by up to 60% and recover recyclable metals from non-degraded electronic modules like chips and batteries.

However, the innovation has a complicated underside. The enzymatic breakdown process releases microscopic nanoparticles—denominated as nanobioparticles (NBPs)—derived from degraded metal wires, fragmented silicon, and nanoscale adhesives. While small, they aren’t necessarily inert.

Environmental scientists warn that NBPs could seep into soil and groundwater. Studies at the University of Copenhagen recently showed that silver nanowires can catalyze oxidative stress in microbial communities at concentrations as low as 5 μg/kg. Meanwhile, early field tests in composting facilities in Germany revealed trace accumulation of lithium and cobalt particles from degraded batteries—with unclear implications for long-term soil health.

Samsung and Xiaomi have responded by implementing multi-tiered filtration packaging systems. The phones come with “destruct pouches” containing activated carbon and biochar layers to capture outgassing, plus guidelines to deposit destructed phones only at licensed compost facilities equipped with nanoparticle digesters. They also maintain an internal app dashboard that tracks degradation status, estimated nanoparticle load, and disposal instructions to encourage proper user behavior.

While regulators have cautiously approved the initiative, public environmentalists are urging a slower roll-out and broader safety testing. They argue that mainstreaming self-destructing phones without robust nano-safety infrastructure could create new pollution hazards even as it solves others. The next evolution could involve full recycling of NBPs into fertilizing amendments or tech-grade materials—closing the loop completely.

The ‘Phone Funeral’ Phenomenon: User Culture Goes Meta

Perhaps the most compelling cultural response comes not from policy but from social media. On Reddit, a viral trend dubbed the “Phone Funeral Challenge” has emerged, attracting thousands of participants worldwide. Users ceremonially trigger the self-destruct command, film the dissolution process, and memorialize the phone’s lifecycle via obituaries, eulogies, and digital testimonials.

One popular video shows a user reciting:

“We met in 2023, and together we scrolled, shared, and survived Roshar challenges. But now, it’s time for you to go back to Earth.”

The clip ends with the remains shown atop a compost heap, tagged with a biodegradable phone case planted with basil seeds grown from the device’s storage tray. These posts are receiving millions of views, driving awareness and emotional buy-in to the concept of phones as consumable, mortal devices with a natural death.

Some phone manufacturers—even traditional recycled-plastic makers—are joining in by offering mail-in sleeve packages that capture user “phone stories” and produce virtual obituaries. Others market “Phone Ash Wishing” promotions tied to planting trees with every destructed device, gamifying the environmental loop.

Critics have pointed out the irony: celebrating device death while still consuming new ones perpetuates a throw-away ethos. But supporters argue it’s a step toward mindful disposal, an ecological ritual that ties consumer life to planetary impact. For many, the emotional closure provided by the ritual offsets the loneliness of constantly upgrading devices.

Conclusion: Balancing Innovation with Responsibility

By 2025, self-destructing smartphones are more than tech novelties—they’re social artifacts, environmental interventions, and consumer culture disruptors. Programmable biodegradation represents a radical approach to circular electronics, one that acknowledges consumer hardware’s finite life rather than ignoring it. But the path forward is not void of risks: nanomaterial pollution, disposal infrastructure gaps, and cultural over-ritualization must be managed.

What remains clear is the shift in mindset. No longer is a smartphone seen as a permanent possession—it’s now a consumable, whose final form is part of its story. Self-destructing phones challenge us to rethink how we value—and ultimately say goodbye to—our tech. The promise is big: phones designed not just for performance, but for death with dignity. If navigated carefully, these devices could mark the beginning of a true generation of circular electronics—where obsolescence doesn’t mean toxicity, and endings are catalysts for regeneration.

Discussion about this post