The allure of the Moon has fascinated humanity for centuries. From ancient myths to modern science fiction, our closest celestial neighbor has been a canvas for dreams of exploration, discovery, and even habitation. With the recent resurgence of interest in lunar exploration—from NASA’s Artemis program to private enterprises like SpaceX and Blue Origin—the concept of a permanent human colony on the Moon is no longer confined to fiction. But the crucial question remains: are we really ready to establish a human colony on the Moon? The answer, as it turns out, is far more complex than simply engineering rockets and building habitats.

The Scientific Case for a Lunar Colony

The Moon is not just a symbol; it is a scientific treasure trove. Its surface preserves a 4.5-billion-year history of the solar system, providing unique insights into planetary formation, space weather, and cosmic impacts. A lunar colony would allow continuous research on regolith, lunar geology, and the effects of low gravity on human physiology. Beyond pure science, the Moon could serve as a launching pad for deeper space exploration, particularly missions to Mars. Its lower gravity—roughly one-sixth of Earth’s—reduces fuel requirements for launches, potentially revolutionizing space logistics.

Yet, the Moon is far from hospitable. Its surface temperature swings wildly, ranging from −173°C at night to 127°C during the day. Micrometeorite impacts and solar radiation add layers of risk. Any colony must not only protect inhabitants from extreme temperatures and radiation but also create a self-sustaining environment. This is a challenge that merges materials science, aerospace engineering, and human biology.

Technological Hurdles: Life Support Systems

Sustaining human life on the Moon is no small feat. Water, oxygen, and food—basic necessities we often take for granted—must either be transported from Earth or sourced locally. While lunar ice deposits near the poles offer a potential water source, extracting and purifying it is technically challenging. Oxygen can be generated from regolith through processes like molten regolith electrolysis, but such systems require substantial energy and robust engineering to operate reliably.

Food production presents its own set of problems. Traditional agriculture is unfeasible in the Moon’s low-gravity, low-pressure environment. Hydroponics and aeroponics are promising alternatives, but they demand precise control over nutrients, light, and water cycles. Integrating these systems into a habitat that can withstand lunar extremes is a monumental engineering task.

Moreover, energy generation is a crucial concern. Solar power is abundant on the Moon’s surface, but the two-week-long lunar nights necessitate advanced energy storage or nuclear power solutions. NASA’s Kilopower project explores compact nuclear reactors, which could provide a continuous energy supply, yet safety, reliability, and scalability remain unresolved questions.

Psychological and Social Challenges

Technological readiness alone is insufficient. Human psychology and sociology must be considered carefully. Isolation, confinement, and extreme environmental stress can profoundly affect mental health. Astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) already experience heightened anxiety and interpersonal friction in a microgravity, enclosed environment. A lunar colony amplifies these challenges, with limited communication delays, longer mission durations, and fewer escape options.

Designing habitats that promote psychological well-being is therefore critical. Incorporating naturalistic lighting cycles, communal spaces, and recreational activities may help maintain morale. Artificial intelligence and augmented reality could provide virtual social interactions and entertainment, helping to mitigate feelings of isolation.

Social dynamics in a closed lunar community also require careful planning. Governance structures, conflict resolution protocols, and cultural considerations must be defined in advance. Unlike space stations, which operate under clear national or international frameworks, a lunar colony may evolve into a semi-autonomous entity, raising legal and ethical questions about sovereignty, resource rights, and human behavior in extraterrestrial settings.

The Economic Imperative

A lunar colony is not only a scientific or symbolic pursuit—it is also an economic venture. Moon resources, particularly helium-3, a potential fuel for nuclear fusion, have attracted interest from energy companies. Rare earth metals and other minerals could also become economically valuable. Establishing mining operations on the Moon could transform the global economy, but only if the costs of extraction, processing, and transport are manageable.

Private companies like SpaceX envision reusable spacecraft lowering launch costs, while Blue Origin emphasizes sustainable lunar infrastructure. Public-private partnerships may be crucial in funding and sustaining long-term operations. However, investment risks are enormous: the initial cost of a lunar base may run into hundreds of billions of dollars, with returns decades away, if at all. This raises a critical question: can we justify the investment now, or are lunar colonies a futuristic luxury we cannot yet afford?

Engineering Habitats: From Concept to Reality

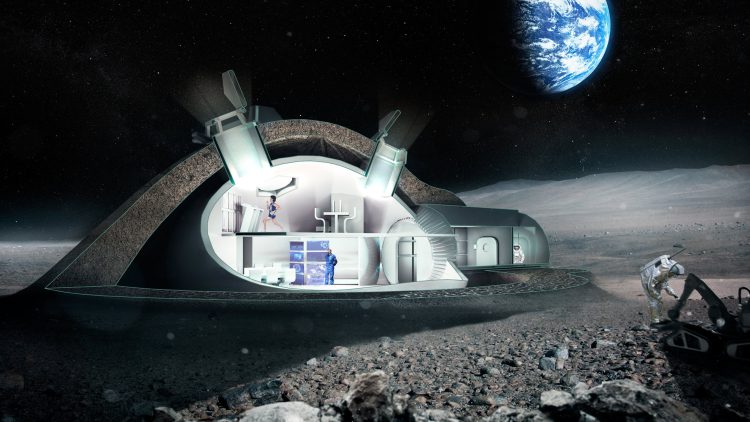

Habitat design on the Moon requires a balance between innovation, safety, and sustainability. Structures must withstand micrometeorite impacts, radiation, and the vacuum of space. Inflatable habitats, 3D-printed regolith shelters, and modular underground bunkers are all under consideration. Each approach has advantages and limitations:

- Inflatable habitats offer flexibility and low mass, but require thick protective layers to shield against radiation.

- 3D-printed regolith shelters leverage local resources, reducing supply costs, yet the technology is still experimental and untested at scale.

- Underground bases provide natural protection but complicate construction and logistics.

Life support systems must be integrated into these habitats, including air recycling, water recovery, waste management, and temperature regulation. AI-driven systems may automate much of the monitoring and maintenance, reducing the need for constant human intervention. Yet, these systems must be extraordinarily reliable—failure in such a hostile environment can be fatal.

The Health Challenge: Human Adaptation to Low Gravity

Long-term exposure to lunar gravity presents unprecedented medical challenges. Reduced gravity affects muscles, bones, cardiovascular function, and the vestibular system, potentially leading to osteoporosis, weakened muscles, and balance disorders. Countermeasures, such as resistive exercise devices, pharmacological interventions, or artificial gravity habitats, are essential.

Radiation exposure is another critical health concern. The Moon lacks a protective magnetic field, exposing colonists to galactic cosmic rays and solar particle events. Shielding, both physical (regolith walls) and chemical (radiation-absorbing materials), is vital. Research from astronauts in low Earth orbit informs these strategies, but lunar conditions are unique and extreme. Long-term health effects remain uncertain.

Political and Legal Considerations

A lunar colony is not just a scientific and technological challenge—it is also a geopolitical one. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits national appropriation of celestial bodies, creating legal ambiguity around resource exploitation. How will nations and private companies share lunar territory, water ice, and mineral deposits? What regulations will govern commerce, environmental protection, and conflict resolution?

International cooperation may be essential, but it also introduces complexity. Competing national interests, corporate ambitions, and the lack of a clear legal framework could hinder progress. Effective governance models must balance innovation, equity, and security, while fostering peaceful collaboration.

Environmental Ethics and Sustainability

The Moon is pristine, and any human presence risks irreversible environmental impact. Dust contamination, habitat construction, and resource extraction could permanently alter lunar landscapes. Ethical considerations demand careful planning to minimize ecological damage and preserve the Moon’s scientific value.

Sustainable lunar operations will likely depend on closed-loop systems for water, oxygen, and food. Waste recycling, renewable energy, and minimal disruption of local geology are essential principles. If we fail to develop environmentally responsible practices, we risk repeating the mistakes of Earth’s industrialization on another world.

Lessons from the International Space Station

The ISS provides a valuable template for lunar colonization. Life support, crew rotation, remote operations, and international collaboration are lessons directly transferable to the Moon. Yet, the Moon presents harsher conditions, including extreme temperature fluctuations, higher radiation, and isolation. Scaling ISS lessons to a lunar base will require innovative engineering, resilient logistics, and robust contingency planning.

The Timeline: When Could a Colony Become Viable?

Optimistic projections suggest that a small lunar outpost could be operational within the next decade. NASA’s Artemis missions aim to return humans to the Moon and establish a sustainable presence by the late 2020s. Private companies may accelerate infrastructure development, creating logistics hubs, habitats, and resource extraction facilities.

However, full-scale colonization—self-sufficient, long-term communities—remains decades away. Achieving true independence from Earth supply chains requires breakthroughs in life support, agriculture, energy storage, and habitat construction. Human adaptation, governance, and ethics must evolve alongside technology to ensure sustainable operations.

Are We Really Ready?

In short, the answer is: not entirely. Technologically, we are closer than ever, with rockets, habitats, AI, and energy solutions reaching experimental maturity. Economically, political will and private investment are growing, yet the risks and costs remain enormous. Socially and psychologically, humanity must adapt to isolation, confinement, and the challenges of lunar life. Legally and ethically, frameworks for governance, resource sharing, and environmental protection are still evolving.

A lunar colony is technically feasible in the near future, but readiness goes beyond engineering. It encompasses human adaptability, international cooperation, sustainable design, and ethical foresight. Until these elements align, the Moon will remain a tantalizing, semi-realistic dream rather than a permanent home.

Yet, the dream itself is transformative. Planning a lunar colony pushes the boundaries of science, technology, and human imagination. It inspires education, innovation, and global collaboration. Even if we are not fully ready today, striving toward readiness will advance knowledge, capability, and vision—not only for the Moon, but for humanity’s future among the stars.

In conclusion, while a permanent human colony on the Moon is conceivable within this century, our readiness is a mosaic of partially solved engineering problems, evolving legal frameworks, emerging economic models, and the uncharted psychology of extraterrestrial life. The Moon is calling, but answering requires more than rockets—it demands preparation of the human spirit, the global community, and the technologies that will let us thrive beyond Earth.

Discussion about this post