A Pioneering Procedure for a Hopeful Future

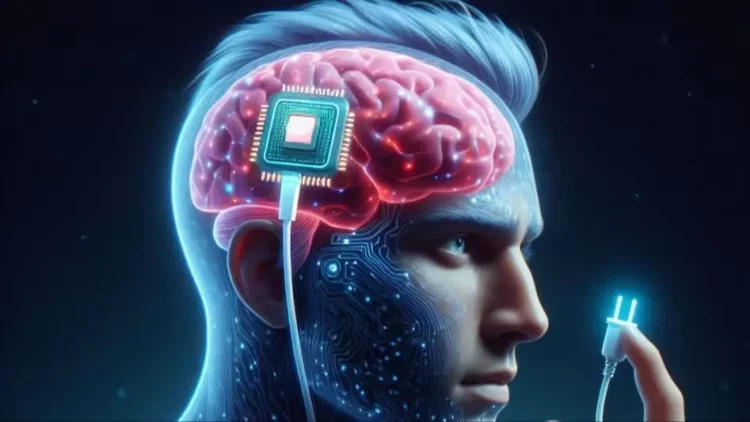

In a landmark surgical endeavor, Oren Noel, a young British boy, has become the first person worldwide to undergo an operation to implant an electronic device within his brain, aiming to mitigate the frequency of epileptic seizures.

Reported by the BBC on the 23rd, Noel was diagnosed at age 3 with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome—a form of epilepsy that typically manifests before school age, characterized by diverse and frequent seizures that prove refractory to medication. Noel’s daily life was besieged by seizures ranging from dozens to hundreds of episodes a day, causing sudden collapses, violent tremors, and loss of consciousness. At times, these episodes were severe enough to halt breathing, necessitating emergency response.

Facing a Compounding Challenge

Justin, his mother, notes that while Oren also faces the challenges of autism and ADHD, the scourge of epilepsy casts the longest shadow. “I had a bright 3-year-old. Within months of the onset of seizures, his condition rapidly deteriorated, robbing him of many capabilities,” she reflected. She views the disease as a thief of Oren’s childhood.

Refusing to relinquish hope, Justin consented for Oren to participate in a research initiative—a collaboration between Great Ormond Street Hospital, University College London, King’s College Hospital, and Oxford University—to test the efficacy of controlling epilepsy with an intracranial electronic device.

A Milestone Operation

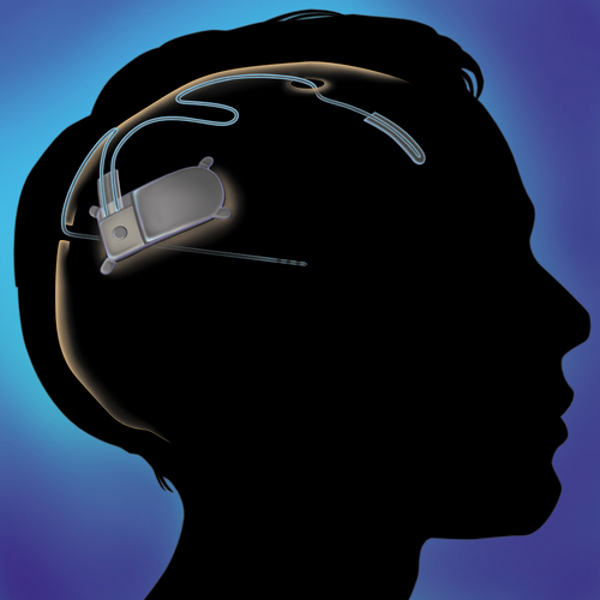

In October of the previous year, 12-year-old Noel underwent an 8-hour surgery at Great Ormond Street Hospital. Led by pediatric neurosurgeon Martin Tisdall, the team placed two electrodes deep in the thalamus, a critical relay station for neuronal information. The electrodes connected to a neurostimulator—a device measuring 3.5 cm square by 0.6 cm thick—implanted within Noel’s skull.

Epileptic seizures originate from aberrant, spontaneous electrical activity in the brain. The implanted device delivers continuous pulse currents designed to interrupt or interfere with these erratic signals.

While this method has been employed in treating childhood epilepsy before, neurostimulators have traditionally been placed in the chest, not the brain.

A New Lease on Life

After a month of convalescence, doctors activated Oren’s brain device, which operates without causing discomfort. Subsequently, his seizure frequency declined by 80%. Daytime falls due to seizures all but ceased, and nocturnal episodes became briefer and less severe. “He’s happier,” Justin says, “and the quality of his life has vastly improved.”

Dr. Tisdall shares that this research may help physicians understand the efficacy of deep brain stimulation in treating such epilepsy and accelerate the development of new therapeutic devices. Going forward, the medical team plans to perform similar implantations for three other children with the same condition.

Additionally, plans to upgrade the neurostimulator to react in real-time to changes in Oren’s brain activity are underway, with the goal of preempting seizures before they occur. Justin’s excitement is palpable: “The team at Great Ormond Street has reignited our hope… Now, the future looks much brighter.”

Discussion about this post